I fell in love with the Boston Marathon in 1964. I was running through the woods with the neighborhood dogs when I first saw it. For me, running was a form of communion with nature and a way to rejoin my mind and body. Hardly anyone ran back then. But I just love to run. I didn’t know the marathon was closed to women, and I set about training in nurses’ shoes with no instructions, no coach, and no books. At first, I had no intention of making any kind of statement, I was following my heart for no other reason than I felt moved by some inner force — passion.

My boyfriend would take me on his motorcycle and drop me off, and I would run home. I gradually increased my distance from one mile to eight and ten, until I was commuting on foot to the Museum School in Boston, where I was studying sculpture. At that time, in 1964, the Vietnam War was raging, President Kennedy had just been assassinated, and the civil rights movement was taking shape. There was no women’s movement yet, and most women expected to be married, but not to work.

As part of my training in 1965, I took a trip in my VW bus alone with my malamute puppy, Moot, from Massachusetts across the entire continent to California. I said to her as I pulled out of my driveway, “Let’s go for a swim, Mooty, … in the Pacific Ocean.” She wagged her tail and licked my face, and off we went. Every day I ran for hours and miles in a new place — the hills of Massachusetts, the grassy fields of the Midwest, the open prairies of Nebraska, the Rocky Mountains, the Sierra Nevada, the coast of California. I’d never seen this earth before, and to me it was wondrous.

I was getting very strong. I could run 40 miles at a stretch. I’d see the top of a distant mountain, small and pale blue in the distance, and I’d spend all day running there, just to stand on the top. Then I’d turn around and run back. I made camp and slept outside every night, feeling infinitely close to nature. I was on a spiritual journey discovering something basic about existence.

Then in February of 1966, from California, where I had moved, I wrote for my application to the Boston Athletic Association (BAA). The Boston Marathon was the only marathon I had ever heard of. Will Cloney, the race director, wrote back a letter that said women were not physiologically capable of running 26 miles and furthermore, under the rules that governed international sports, they were not allowed to run.

I was stunned.

“All the more reason to run,” I thought.

At that moment, I knew I was running for much more than my own personal challenge. I was running to change the way people think. There existed a false belief that was keeping half the world’s population from experiencing all of life. And I believed if everyone, man and woman, could find the peace and wholeness I found in running, the world would be a better, happier, healthier place.

It was a catch 22: How can you prove you can do something if you’re not allowed to do it? If women could do this that was thought impossible, what else could women do? What else can people do that is thought impossible?

I took the bus back from San Diego, curled up in the seat for three nights and four days, eating only a bag of apples and bus station chili and arrived the day before the race at my parents’ house in Winchester. I ate a huge roast beef dinner and apple pie. The next day my mother drove me to the start in Hopkinton and dropped me off. I ran up and down a couple of miles to warm up, and then I hid in the bushes near the start.

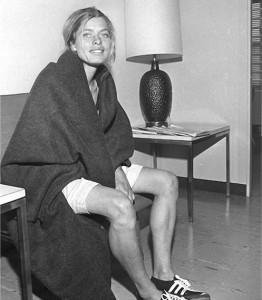

When the gun went off, I jumped into the pack. I had no idea what kind of reception I’d get. I was afraid the police would arrest me and the spectators might boo and hiss. I was afraid if the officials saw I was a woman, they’d throw me out. I was all alone. I knew the most important thing was to prevent anyone from stopping me, so I wore a blue sweatshirt with the hood pulled up and my brother’s Bermuda shorts tied up with a string, over my black, tank-topped bathing suit.

When the gun went off, I jumped into the pack. I had no idea what kind of reception I’d get. I was afraid the police would arrest me and the spectators might boo and hiss. I was afraid if the officials saw I was a woman, they’d throw me out. I was all alone. I knew the most important thing was to prevent anyone from stopping me, so I wore a blue sweatshirt with the hood pulled up and my brother’s Bermuda shorts tied up with a string, over my black, tank-topped bathing suit.

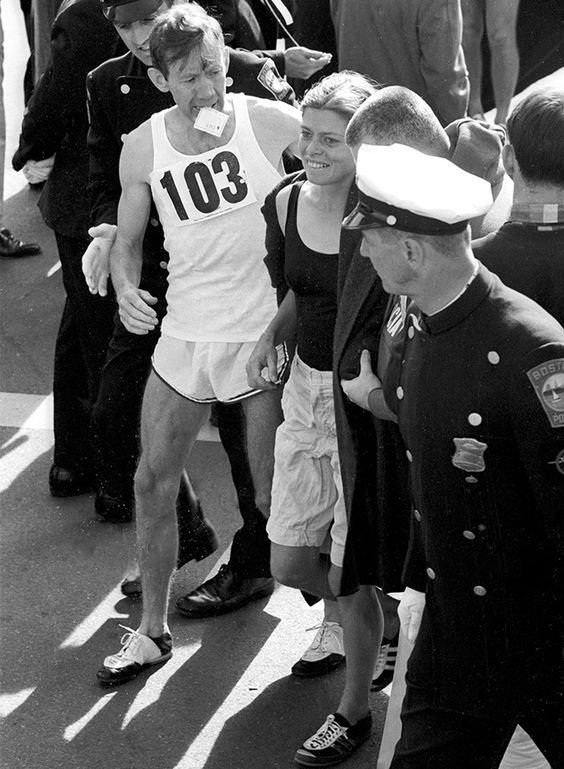

Very quickly, the men behind me, studying my anatomy, figured out t I was a woman, and to my great relief, they were supportive and friendly. They could have shouldered me off the course, but instead they said, “It’s a free road. We won’t let anyone throw you out.” So contrary to what some people think, it was not a men-versus-women confrontation. The men were glad I was running. With this encouragement, I took off the hot, heavy sweatshirt, and then everyone could see that I was a woman. A cheer went up from the crowd when they saw a woman was running.

Reporters spotted me and phoned the story on ahead. The radio was broadcasting my progress towards Boston. When I got to Wellesley College the women knew I was coming and were watching for me. They were screaming and crying. One woman, standing near with several children, yelled, “Ave Maria.” She was crying. I felt as though I was setting them free. Tears pressed behind my own eyes.

I was running conservatively because I knew if I failed to finish, I would reinforce the prejudices and set women’s running back another 20 years. The weight of responsibility sat heavily on my back. Even so, I ran most of the race at a sub-three-hour pace. But in the last three miles, my pace dropped off. I had severe blisters, and I had not had any water to drink, since I was misinformed into believing it would give me cramps to drink while exercising.

I was running conservatively because I knew if I failed to finish, I would reinforce the prejudices and set women’s running back another 20 years. The weight of responsibility sat heavily on my back. Even so, I ran most of the race at a sub-three-hour pace. But in the last three miles, my pace dropped off. I had severe blisters, and I had not had any water to drink, since I was misinformed into believing it would give me cramps to drink while exercising.

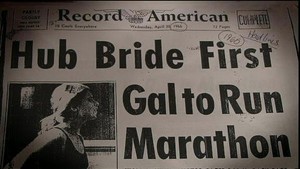

Finally, I got to Hereford Street and made the turn on to Boylston. Spectators thronged the bleachers and let out a roar of applause. The press was there. The governor of Massachusetts came down to shake my hand. The next day it was front-page headlines. News went out around the world that a woman had run the Boston Marathon. I had run in a time of 3 hours and 21 minutes and had finished ahead of two-thirds of the field.

Finally, I got to Hereford Street and made the turn on to Boylston. Spectators thronged the bleachers and let out a roar of applause. The press was there. The governor of Massachusetts came down to shake my hand. The next day it was front-page headlines. News went out around the world that a woman had run the Boston Marathon. I had run in a time of 3 hours and 21 minutes and had finished ahead of two-thirds of the field.

It was a pivotal point in the evolution of social consciousness. It changed the way men thought about women, and it changed the way women thought about themselves. It replaced an old false belief with a new reality.

It was a pivotal point in the evolution of social consciousness. It changed the way men thought about women, and it changed the way women thought about themselves. It replaced an old false belief with a new reality.

By 1967, everyone already knew a woman could run a marathon. The press was expecting me to run again and was waiting for me. This time, there was no opposition to my running. I did not have to disguise myself; I just stood to one side and, when the gun went off, started to run. I ran again without a number however, because there were no official numbers for women. I finished one hour ahead of the other female competitor, K.V. Switzer, who had obtained a number by disguising her gender at registration.

By 1967, everyone already knew a woman could run a marathon. The press was expecting me to run again and was waiting for me. This time, there was no opposition to my running. I did not have to disguise myself; I just stood to one side and, when the gun went off, started to run. I ran again without a number however, because there were no official numbers for women. I finished one hour ahead of the other female competitor, K.V. Switzer, who had obtained a number by disguising her gender at registration.

The next year, 1968, I ran again, still without a number, and again finished first out of five women who were all running without numbers. It was important not only that a woman run, but that she ran well. I was not running to launch a career or to get publicity for myself. Nor was I running for money. There was no prize money in those days. I was running because that’s what I loved to do, and I was running to set women free and to overturn the false beliefs that kept half the world’s population in bondage. I wanted to demonstrate in a dignified, competent way a woman could run the 26-mile distance. Once people understood that, I felt sure the race would open up.

Sara Mae Berman continued the tradition I had started by running in 1969, 1970 and 1971 with very good times. The race opened to women officially in 1972, and Nina Kusick became the first official female winner.

But in fairness, it should be noted that prior to 1966, people did not know a woman was capable of running 26 miles. Even women didn’t know it, and many women officials were opposed to it out of fear an attempt would cause injury or death. It should also be noted the men in that first race were supportive and friendly and were not opposed to a woman running if she were well-trained. Indeed, the men admired a woman who could run as they did, with strength and grace and dignity. So it was ignorance and a false belief that had to be overcome.

During that time, I was studying pre-med and mathematics at the University of California in La Jolla, and received my bachelor’s in 1969. Denied entrance to medical school because I was woman, I worked for a few years, married and got my law degree. The best thing I ever did was to have a child. It’s the most wonderful, loving, satisfying thing in the world.

Since that time, I’ve run many marathons and continue to run as a meditation. I run almost every day for an hour or more. The last time I ran Boston was in 2001, the 35th anniversary of my first run in 1966. My running now is for charity — the fight against Lou Gehrig’s disease, causes and cures of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, children with cancer, and helping shelters for women and children and families in distress.

I have always had a vision of a world where men and women can share all of life together in mutual respect, love and admiration; a world where we find health through exercise and through the appreciation of the spirit and beauty of the world and of each other; a world based on love and individual integrity, where we all have a chance to do what we most passionately love, to help others, and to become all we can become.

We talk a lot about peace. But what is peace? It is not just a passive state of acquiescence. Peace is a dynamic state of human interrelationship, based on fairness and consideration, which requires the hard work of becoming fully who we are, and encouraging others to do the same. This is still my vision — a world free of oppression, full of beauty and based on love. And, this is what I work for in every way I can. I wish everyone well and hope you are all healthy, happy and doing what you love!

Roberta Gibb

San Diego, California

April 19, 1966

Age – 23

Bib # (None)

3:21:40

This story was originally published by the Women’s Sports Foundation.

A reflection and expression of thanks by Bobbi Gibb for the recognition she received at the 2016 Boston Marathon on the 50th anniversary of her 1966 Boston can be found here: Bobbi Gibb Art.