In 2009 when I decided to run my first marathon, my goal from the start was to see if I could qualify for the Boston Marathon. Boston is the dream for so many people, because it is legendary. It is the oldest, longest running marathon in the world, and it is the only one, other than the Olympics, for which you must qualify. Most of us have little chance of that. For the average runner, Boston has become the brass ring. I wanted to know if I could do it: not just finish a marathon, but be fast enough to go to Boston. I ran my first marathon in May of 2009, missing the Boston qualifying mark by seven and a half minutes. After recuperating from shin splints, I decided that summer to try again in Victoria. Although I only had nine weeks to train, I got my Boston qualifying time with a minute to spare.

Training for marathons fills me with a tremendous amount of energy, anticipation and fear. Training for Boston heightened everything. My training for the most part was great. The only drawback was a lousy winter that left me on the treadmill mile after mile, something that would come back to haunt me. But, I never felt better, or stronger, and I had some phenomenal weeks of training, running many personal bests. I was ready for Boston, but I was filled with fear my training was not enough, that I had done things wrong, peaked too soon, or any other doubt my mind could create. These doubts are emotional junk, and are part of the hardest lesson of running, or life, the importance of letting go of the outcome.

So I arrived in Boston, my wonderful family in tow to cheer me on, ready for whatever awaited me on race day. I tried not to over think or get too stressed about the race; knowing I had done all I could at that point, and it was now time to simply believe. Believing for me was all about my goal time. I had set an ambitious goal of finishing under 3:20, a time that would best my personal record by almost ten minutes. If everything went in my favor and I had a perfect day, I felt it was realistic and in my grasp. I visualized that time on the clock as I crossed the finish line.

Finally the morning of the race arrived and I made the drive from Newton, where we stayed, to Hopkinton, filled with positive energy, and satisfied I was living my dream. Arriving in Athletes’ Village in Hopkinton was the first awe-inspiring sight. “It all starts in Hopkinton” reads the famous sign at the start of the marathon course. The village was set up at the small town’s middle school. The field was filled with tents and people. A Jumbotron in the middle of the field was showing text messages wishing people well. Boston is not the biggest marathon, but it was the biggest I had ever been in by a large margin, and to see 27,000 runners was tremendous. The morning air was cool, and intensified by a brisk wind. I was thankful I had enough warm clothes because so many people were shivering trying to find any way they could to keep warm. I was perfectly warm right up to the start.

Finally the morning of the race arrived and I made the drive from Newton, where we stayed, to Hopkinton, filled with positive energy, and satisfied I was living my dream. Arriving in Athletes’ Village in Hopkinton was the first awe-inspiring sight. “It all starts in Hopkinton” reads the famous sign at the start of the marathon course. The village was set up at the small town’s middle school. The field was filled with tents and people. A Jumbotron in the middle of the field was showing text messages wishing people well. Boston is not the biggest marathon, but it was the biggest I had ever been in by a large margin, and to see 27,000 runners was tremendous. The morning air was cool, and intensified by a brisk wind. I was thankful I had enough warm clothes because so many people were shivering trying to find any way they could to keep warm. I was perfectly warm right up to the start.

After a two-hour wait in Athletes’ Village, the excitement began to build as the elite and first wave runners were ushered to the starting line. It was getting close to the start for the first wave when I began making my way to the starting corrals with the second wave of runners. As I walked from the school to the main street I heard the starting pistol go off, and we all let out a huge cheer as the marathon was now under way.

I was only twenty minutes from my starting time. I made my way to the porta potties one last time, the timing of which is a critical thing for runners, navigating the massive line ups, and then walked up the beautiful and historic main street towards the third corral where I was to line up for the start. I peeled off the last layers of warm clothing, and tossed them on the big piles of throwaway clothes that were been gathered for donation. I stepped into my corral with the other thousand people, and anxiously awaited the start. My heart was racing, and I felt a rush of adrenaline. I could feel the energy of the nine thousand runners in my wave ready to propel themselves 26.2 miles to Boston.

I began to get emotional. First of all, there were lots of people waiting to cheer us on. Hopkinton was beautiful, and the day was spectacular: Blue skies and a tail wind, great racing conditions. Finally it was start time and my emotions really caught me. My eyes welled up. I was so grateful to be there ready to run one of the greatest marathons in the world. Finally the pistol for the second wave went off, and I cheered from my toes. Seeing the massive wave of thousands of bopping bodies in front of me was incredible. The start was slow with all of the people, but soon we were starting to jog, and began the first big downhill portion of the race.

I began to get emotional. First of all, there were lots of people waiting to cheer us on. Hopkinton was beautiful, and the day was spectacular: Blue skies and a tail wind, great racing conditions. Finally it was start time and my emotions really caught me. My eyes welled up. I was so grateful to be there ready to run one of the greatest marathons in the world. Finally the pistol for the second wave went off, and I cheered from my toes. Seeing the massive wave of thousands of bopping bodies in front of me was incredible. The start was slow with all of the people, but soon we were starting to jog, and began the first big downhill portion of the race.

I was immediately caught by how many people were watching. I had heard there would be lots of spectators, but I had no idea just how amazing and loud the fans were going to be. All along the route there were people cheering us on: Little kids, bikers, fiddlers, students, seniors; people of all sorts everywhere all along the route. At times it seemed as if every person in every small town along the way had come out to cheer us on. I know I ran the first twenty miles with a big smile. I didn’t feel like I was running at all. I felt effortless, almost as if I was floating. It was such a wonderful atmosphere, unlike anything I have ever experienced.

Some of the highlights were running through Natick where the fans lined the streets three and four deep, and then Wellesley College. Wellesley is famous for having all of the girls at the school coming out to scream for the duration of the race. The Wellesley “scream tunnel” was everything it had been hyped as, so many girls with signs asking for kisses, and screaming. I was running so well and so focused at that point, but I still shouted out encouragement and thanks to them. Wellesley is also the halfway point of the marathon, and I was right on time. My excitement grew.

I ran very smoothly during the race. Because all of my training had been on the treadmill I was concerned I would not be able to find my pace easily, but I settled right into the exact pace I had planned. I never felt at all like I was pushing myself. I was at a comfortable pace for twenty-two miles. It was freeing to feel so good and strong for so long. I felt like I was running with an even effort, something I had learned from reading accounts of others who had run the course. Boston is a notoriously tough course because of the hills. While it is a net downhill course, there are a lot of rolling sections. The downhills are harder on the quads, especially if you have not trained for them. I think this is partly why Kenyans do so well in Boston. They run hills everyday growing up and in training. So running an even effort, rather than an even pace should give you an advantage over the length of the course, not too fast on the downhills – controlled, and not too hard on the uphill portions.

The Newton Hills is the famous section of the course. They go from mile 16 to mile 21, and are a series of four long hills, finishing with the famous Heartbreak Hill. They are not necessarily monstrous hills, but they are tough because of where they come in the race. When I got to about the third of the four Newton hills, I could feel my pace slowing, but it was partly a conscious decision to not push too hard up the hills so I would still be strong for the end. I kept looking for Jennifer, Benjamin, Nicholas, Lynn and my Dad, and was so happy when I finally saw them. I stopped quickly to give Ben and Nick a kiss and then started on my way again. I had to really slug hard to get up Heartbreak Hill. I could feel the effects now from not having done much roadwork, as my legs got a bit heavy, and I could feel my quads and hips starting to burn. This is where the treadmill training really killed me. Getting to the top of Heartbreak Hill was great, and I tried to lift my spirits by yelling out to the crowd “Where’s the hill?”

We were now at Boston College, greeted by a big inflatable archway that had the words “The Heartbreak is Over.” There were thousands of very rowdy, likely drunk college students screaming encouragement, and I could see the nice and inviting downhill in front of me. But, the downhill was almost more painful at that point. My legs felt the pounding as much as I tried to keep my pace easy. But after a bit, I seemed to settle in and I was still running under eight-minute miles at that point, still maybe 7:50, and that made me happy. I knew if I could hold that pace I was in for a record day. My smile had faded by this point, and as much as the cheers were great, I was focusing intensely now on staying strong, and much of the cheering faded from my consciousness.

We were now at Boston College, greeted by a big inflatable archway that had the words “The Heartbreak is Over.” There were thousands of very rowdy, likely drunk college students screaming encouragement, and I could see the nice and inviting downhill in front of me. But, the downhill was almost more painful at that point. My legs felt the pounding as much as I tried to keep my pace easy. But after a bit, I seemed to settle in and I was still running under eight-minute miles at that point, still maybe 7:50, and that made me happy. I knew if I could hold that pace I was in for a record day. My smile had faded by this point, and as much as the cheers were great, I was focusing intensely now on staying strong, and much of the cheering faded from my consciousness.

We finally turned onto Beacon Street heading towards downtown Boston, Fenway Park and the 22 mile mark. I knew I just had to hold onto my pace. I kept pushing but my pace slowly slipped and before long I was running 9:15 miles. I was pushing as hard as I could to try and get back, but there was nothing left in the tank. The CITGO sign is a famous marathon landmark and it is as evil as everyone says because it is at the last mile mark, but it looms in the distance for so long. I kept running, but for the longest time it seemed like I was never going to get past the CITGO sign.

By the time I got to Fenway Park and the CITGO sign and mile 25, I had nothing left to give. I had never walked in any of my previous three marathons, but I knew it was my only choice now. I did not even have enough energy for the “survivor shuffle.” But, there was no way I was not going to finish the race. The noise from the fans was deafening at this point. They traditionally have a morning Red Sox game on marathon day so that the game ends and 40,000 fans stream out onto Beacon Street as the runners are coming by. All I could see in front of me was a stream of runners through a sea of people.

I kept pushing and there was one last underpass, very cruel at that point to run any kind of hill, and then the last two corners on to Boylston Street. When I made the last turn towards the finish line, I was exhausted and the crowd noise was almost too much to process, yet enthralling. The Boston Marathon finish line was so close now.

I was determined to run over the finish line and enjoy that moment, so I stirred every last bit of energy, and started a slow shuffle run. As soon as I called upon my muscles to carry me those last few hundred feet, my legs revolted, my calves cramped, cramping right up into my lower quads. I wasn’t going to let that stop me, and I shut out the pain and carried myself across the line, my arms in the air in victory. I had done it. I gave every last ounce of energy I had to give.

I was determined to run over the finish line and enjoy that moment, so I stirred every last bit of energy, and started a slow shuffle run. As soon as I called upon my muscles to carry me those last few hundred feet, my legs revolted, my calves cramped, cramping right up into my lower quads. I wasn’t going to let that stop me, and I shut out the pain and carried myself across the line, my arms in the air in victory. I had done it. I gave every last ounce of energy I had to give.

After I crossed the finish line, I made my way through the phalanx of people and support personnel. I saw numerous runners in tough shape getting medical attention, being carried off or wheeled in wheelchairs. I was not far from that state myself. But most of all I saw thousands of faces filled with jubilation. A big green Adidas sign read “Boston with Pride,” and I could see that pride on every runner’s face. Volunteers handed out water, Gatorade, reflective blankets, and bags of food. I tried to get some food in my stomach, but it was hard. Finally after a long walk I got to the medals. I watched as people had the coveted finisher’s medal hung around their necks, and before I realized it, I was weeping. I took off my hat as the volunteer placed the medal over my head, and she congratulated me on a great effort. I began to sob uncontrollably for a moment. I had done something I never imagined possible when I was younger and first followed the Boston Marathon. It was a race for the best runners in the world, and I had no business thinking I would ever do it. But now twenty-years later, I had a Boston Marathon finisher’s medal hanging proudly on my neck.

I did not get the PR I had hoped and trained for, sub 3:20. For so long in the race I felt it was my day. And it was my day. PR’s are great, but it is not why I run the marathon. I run to push myself and see where my limits are and if I can push even a little further. For those who don’t run marathons, or run at all they look at me like I am crazy when I tell them that much of marathon running is about enduring pain. But I have found in life that enduring pain often leads to the sweetest moments. When I am in that moment of pain during the marathon I often say, “I will never do this again.” or “Why am I doing this?” But those moments pass, and then I come to understand I can endure a lot. I have the ability to push myself beyond my doubts, beyond not just my physical limits, but perhaps more importantly, I can push past my emotional limits. I feel so proud of what I did, and have learned to accept and acknowledge every last moment of that pain as a gift. From the pain comes satisfaction that I gave it my all; that I left nothing, no regret on the course. I accepted what the day gave me, not a personal best time, but definitely a personal best. The pain is a lesson in humility, and gratitude. The gratitude for life. The gratitude for getting to run the greatest marathon in the world. The gratitude for the support and love of my family. The gratitude for the wondrous machines we have been give to carry us through life, and when we treat our bodies and our minds with respect, there is little that is not possible.

I did not get the PR I had hoped and trained for, sub 3:20. For so long in the race I felt it was my day. And it was my day. PR’s are great, but it is not why I run the marathon. I run to push myself and see where my limits are and if I can push even a little further. For those who don’t run marathons, or run at all they look at me like I am crazy when I tell them that much of marathon running is about enduring pain. But I have found in life that enduring pain often leads to the sweetest moments. When I am in that moment of pain during the marathon I often say, “I will never do this again.” or “Why am I doing this?” But those moments pass, and then I come to understand I can endure a lot. I have the ability to push myself beyond my doubts, beyond not just my physical limits, but perhaps more importantly, I can push past my emotional limits. I feel so proud of what I did, and have learned to accept and acknowledge every last moment of that pain as a gift. From the pain comes satisfaction that I gave it my all; that I left nothing, no regret on the course. I accepted what the day gave me, not a personal best time, but definitely a personal best. The pain is a lesson in humility, and gratitude. The gratitude for life. The gratitude for getting to run the greatest marathon in the world. The gratitude for the support and love of my family. The gratitude for the wondrous machines we have been give to carry us through life, and when we treat our bodies and our minds with respect, there is little that is not possible.

The marathon is a celebration of the human spirit. Human resiliency gets pushed to the limit, and when you hit the wall, it is sheer will and determination that pulls you forward. It is an event that forces you to push past the fears and doubts in your mind, to ignore the desire to stop, give up, to end the pain. The marathon is an individual accomplishment that demonstrates in the most concrete fashion that anything is possible.

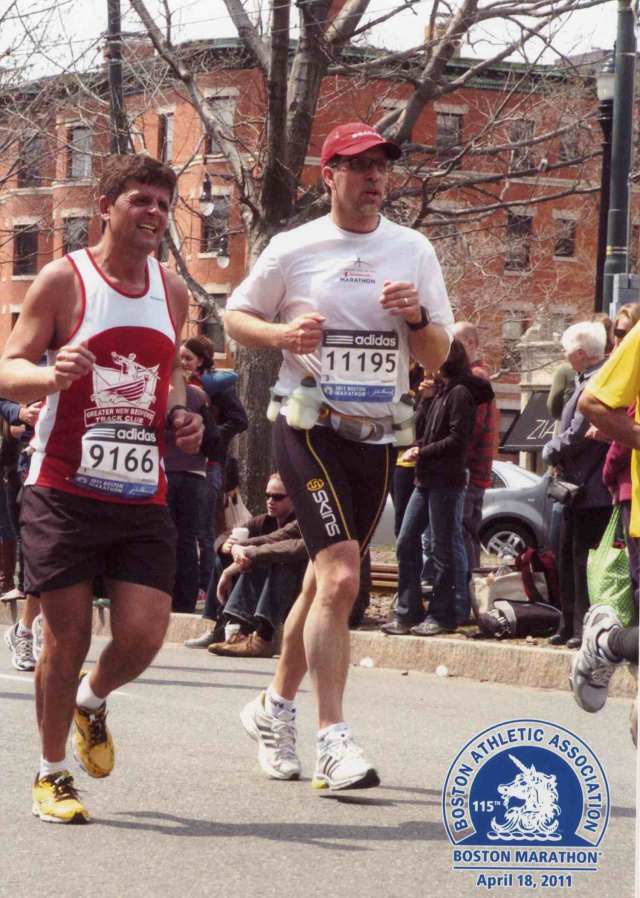

Matt Palmer

Calgary, Alberta

April 18, 2011

Age – 47

Bib # 11195

3:34:07